The study identifies “denying, distortion and distraction” as main strategies!

The alcohol industry (AI) is misrepresenting evidence about the alcohol-related risk of cancer with activities that have parallels with those of the tobacco industry, according to new research published in the journal Drug and Alcohol Review.

Led by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine with the Karolinska Institutet, Sweden, the team analysed the information relating to cancer which appears on the websites and documents of nearly 30 alcohol industry organisations around the world between September 2016 and December 2016. Most of the organisational websites (24/26) showed some sort of distortion or misrepresentation of the evidence about alcohol-related cancer risk, with breast and colorectal cancers being the most common focus of misrepresentation.

The most common approach involves presenting the relationship between alcohol and cancer as highly complex, with the implication or statement that there is no evidence of a consistent or independent link. Others include denying that any relationship exists or claiming inaccurately that there is no risk for light or ‘moderate’ drinking, as well discussing a wide range of real and potential risk factors, thus presenting alcohol as just one risk among many.

According to the study, the researchers say policymakers and public health bodies should reconsider their relationships to these alcohol industry bodies, as the industry is involved in developing alcohol policy in many countries, and disseminates health information to the public.

Alcohol consumption is a well-established risk factor for a range of cancers, including oral cavity, liver, breast and colorectal cancers, and accounts for about 4% of new cancer cases annually in the UK1. There is limited evidence that alcohol consumption protects against some cancers, such as renal and ovary cancers, but in 2016 the UK’s Committee on Carcinogenicity concluded that the evidence is inconsistent, and the increased risk of other cancers as a result of drinking alcohol far outweighs any possible decreased risk².

This new study analysed the information which is disseminated by 27 AI-funded organisations, most commonly ‘social aspects and public relations organisations’ (SAPROs), and similar bodies. The researchers aimed to determine the extent to which the alcohol industry fully and accurately communicates the scientific evidence on alcohol and cancer to consumers. They analysed information on cancer and alcohol consumption disseminated by alcohol industry bodies and related organisations from English speaking countries, or where the information was available in English.

Through qualitative analysis of this information they identified three main industry strategies. Denying, or disputing any link with cancer, or selective omission of the relationship, Distortion: mentioning some risk of cancer, but misrepresenting or obfuscating the nature or size of that risk and Distraction: focusing discussion away from the independent effects of alcohol on common cancers.

Mark Petticrew, Professor of Public Health at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and lead author of the study, said: “The weight of scientific evidence is clear – drinking alcohol increases the risk of some of the most common forms of cancer, including several common cancers. Public awareness of this risk is low, and it has been argued that greater public awareness, particularly of the risk of breast cancer, poses a significant threat to the alcohol industry. Our analysis suggests that the major global alcohol producers may attempt to mitigate this by disseminating misleading information about cancer through their ‘responsible drinking’ bodies.”

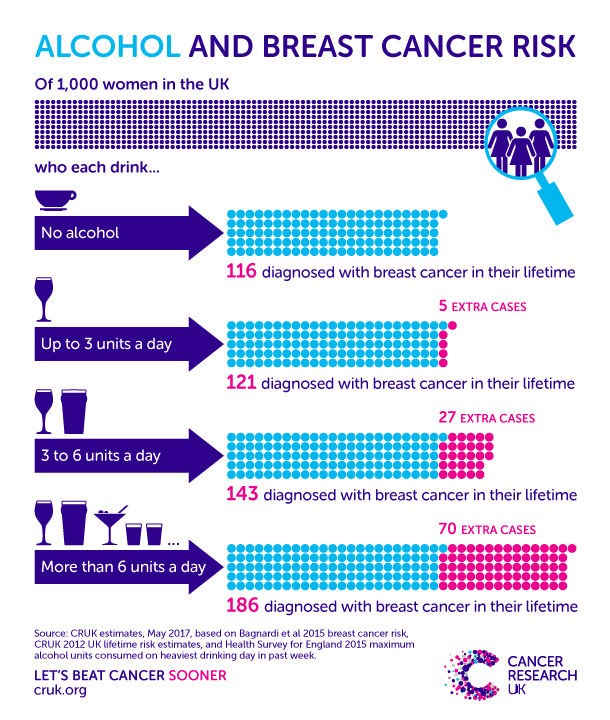

A common strategy was ‘selective omission’ – avoiding mention of cancer while discussing other health risks or appearing to selectively omit specific cancers. The researchers say that one of the most important findings is that AI materials appear to specifically omit or misrepresent the evidence on breast and colorectal cancer. One possible reason is that these are among the most common cancers, and therefore may be more well-known than oral and oesophageal cancers.

When breast cancer is mentioned the researchers found that 21 of the organisations present no, or misleading, information on breast cancer, such as presenting many alternative possible risk factors for breast cancer, without acknowledging the independent risk of alcohol consumption.

Professor Petticrew said: “Existing evidence of strategies employed by the alcohol industry suggests that this may not be a matter of simple error. This has obvious parallels with the global tobacco industry’s decades-long campaign to mislead the public about the risk of cancer, which also used front organisations and corporate social activities.”

The researchers say the results are important because the alcohol industry is involved in conveying health information to people around the world. The findings also suggest that major international alcohol companies may be misleading their shareholders about the risks of their products, potentially leaving the industry open to litigation in some countries.

Professor Petticrew said: “Some public health bodies liaise with the industry organisations that we analysed. Despite their undoubtedly good intentions, it is unethical for them to lend their expertise and legitimacy to industry campaigns which mislead the public about alcohol-related harms. Our findings are also a clear reminder of the risks of giving the AI the responsibility of informing the public about alcohol and health.

“It has often been assumed that, by and large, the AI, unlike the tobacco industry, has tended not to deny the harms of alcohol. However, through its provision of misleading information it can maintain what has been called ‘the illusion of righteousness’ in the eyes of policymakers, while negating any significant impact on alcohol consumption and profits.

“It’s important to highlight that if people drink within the recommended guidelines they shouldn’t be too concerned when it comes to cancer. For accurate and accessible information on the risks, the public can visit the NHS website.”

The authors acknowledge limitations of their study including that there are many other mechanisms and organisations through which industry disseminates health-related information which they did not examine, although it is unlikely that the messages would be different.

The researchers also say there is an urgent need to examine other industry websites, documents, social media and other materials in order to assess the nature and extent of the distortion of evidence, and whether it extends to other health information, for example, in relation to cardiovascular disease.

Publication:

Mark Petticrew, Nason Maani Hessari ,Cécile knai and Elisabete Weiderpass. How alcohol industry organisations mislead the public about alcohol and cancer. Drug and Alcohol Review. DOI: 10.1111/dar.12596

2Committee on Carcinogenicity of chemicals in food, consumer products and the environment (COC). Statement 2015/S2.

About the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine:

The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine is a world-leading centre for research and postgraduate education in public and global health, with more than 4,000 students and 1,000 staff working in over 100 countries. The School is one of the highest-rated research institutions in the UK, is among the world’s leading schools in public and global health, and was named University of the Year in the Times Higher Education Awards 2016. Our mission is to improve health and health equity in the UK and worldwide; working in partnership to achieve excellence in public and global health research, education and translation of knowledge into policy and practice. http://www.lshtm.ac.uk

The report, published by the Foundation for Liver Research, predicts that 32,475 of the deaths – the equivalent of 35 a day – will be the result of liver cancer and another 22,519 from alcoholic liver disease.

The report, published by the Foundation for Liver Research, predicts that 32,475 of the deaths – the equivalent of 35 a day – will be the result of liver cancer and another 22,519 from alcoholic liver disease.

week, which discussed a report that reinforced the evidence that alcohol can increase a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer.

week, which discussed a report that reinforced the evidence that alcohol can increase a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer.